As government mulls its options to reduce expenditure while funding priority programmes, experts have warned that the abolishment of the medical tax credit could be highly problematic and may even face legal challenge in the absence of alternative solutions.

Medical scheme members currently receive a medical tax credit of R303 per month for the first two beneficiaries and R204 per month for the remaining medical scheme members. In contrast to a tax deduction, which lowers a taxpayer’s taxable income, a tax credit reduces an individual’s tax liability. The medical tax credit allows all taxpayers the same benefit in rand, regardless of their income level.

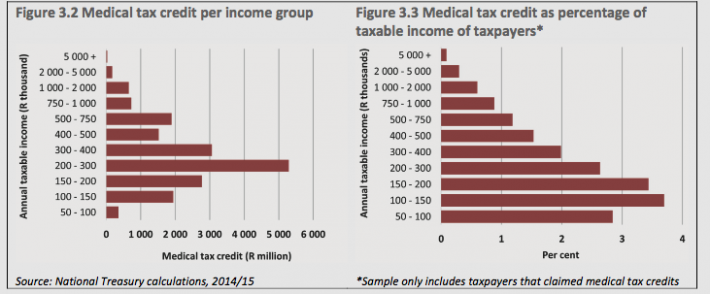

According to National Treasury, three million taxpayers claimed the credit on behalf of eight million medical scheme members in 2014/15, which required tax expenditure of R18.5 billion. Government is under significant pressure to find additional revenue sources and cut spending in order to stabilise its fiscal position, overcome a massive tax revenue shortfall and fund policy priorities.

Treasury previously said it was considering the possible reduction of the medical tax credit as part of the financing framework for the National Health Insurance (NHI). The Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) added that it was deliberating on “changes to the design, targeting and value of the medical tax credit as part of the policy development process for the 2018 budget”.

“Tax data, however, indicates that the programme is well-targeted to lower- and middle-income taxpayers,” it added.

Source: National Treasury (MTBPS)

While Treasury indicated that it would look to the Davis Tax Committee (DTC) for guidance, the DTC did not make an explicit recommendation on medical tax credits in November. It noted however that alignment with the NHI had to be carefully considered and that it could be achieved in a variety of ways, ranging from abolishing the tax credit to viewing it as one of the mechanisms for providing healthcare.

While there is still significant uncertainty about government’s funding priorities, which would only be clarified in the upcoming budget, Prof Alex van den Heever, chair of social security at the Wits School of Governance, says if the medical tax credit was abolished, it would suggest that there was no proper consideration of the implications for the right to healthcare for people who are dependent on the credit to be able to access a medical scheme.

“I think it would be problematic if it were done and it may face legal challenge.”

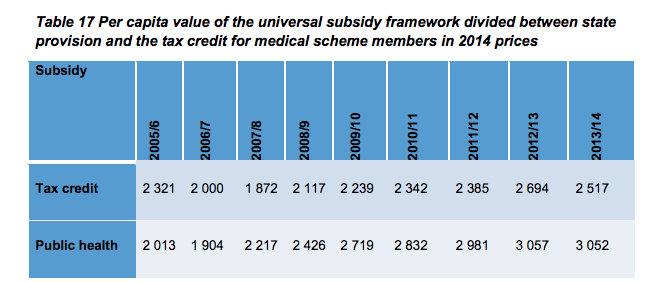

The credit is essentially an entitlement – an allocation provided to people who are dependent on medical schemes for their health coverage. It is compensation for not being able to access the public health service. The capital level is below that of the expenditure on the public health system, he says.

“If it were removed people will lose general access to coverage, which would be highly problematic.”

Moreover, no expenditure programme has yet been identified to which the funds could be allocated to compensate people for the coverage they would lose, he adds.

Even if the credit were only removed for individuals earning more than R300 000 per annum, the picture would not change substantially, as no coherent policy has been formulated.

Van den Heever says when medical schemes are combined with public sector health services, people have universal access to healthcare. The state can’t cover everybody in South Africa – therefore it relies on the fact that some people don’t use the public sector and make use of medical schemes.

“That is the reason why the tax subsidy is provided to people.”

Van den Heever says for middle- and even upper middle-income groups as well as people in retirement, medical scheme coverage gets expensive very quickly.

“Basically, that is part of a universal entitlement scheme as it exists now. So unless you’ve got an alternative model that will replace it the minute you remove it – the subsidy – it is potentially challengeable in terms of the Constitution.”

Ashleigh Theophanides, director and healthcare specialist at Deloitte, does not expect the credit to be abolished.

Some of the research on the topic shows that the unintended consequences of such a step on lower income South Africans are quite significant, she says.

“It is not just about the financial components. It is also about their ability to get access to healthcare in a speedy way.”

Dr Paula Armstrong, economist at Econex, says at this stage it is “entirely unclear” whether government would abolish the credit in an effort to cut expenditure. As a proportion of its overall expenditure, the roughly R18 billion “spent” on the medical tax credit is quite small.

While abolishing the incentive would likely interfere with the affordability of medical schemes, it is just one of many measures government has proposed to fund the NHI.

A study previously conducted by Econex suggested that roughly 1.9 million people (more than 20% of medical scheme beneficiaries) were at risk of losing their private medical scheme membership if tax credits were removed without the introduction of alternative policies, but Armstrong says it is in no way suggesting that this would actually happen.

“It is very unlikely that that will be the only measure put in place by government.”

Armstrong says there has been a call by government to investigate the impact of other policy recommendations, which would likely mitigate some of the potential consequences of scrapping the tax credit.

“You would have to consider what the net impact of all of those policies would be.”